About

I am an Associate Professor of Economics at Stanford Graduate School of Business. I am also a Faculty Research Fellow at the National Bureau of Economic Research and the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research.

My research applies Industrial Organization principles to examine market frictions including risk sharing, congestion and information asymmetries across policy settings including urban development, insurance and online news.

Publications

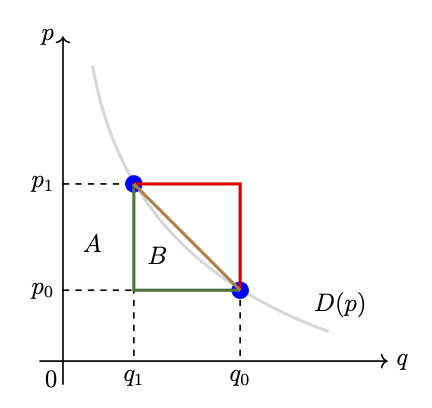

Scaling Auctions as Insurance: A Case Study in Infrastructure Procurement

Econometrica 91.4 (2023): 1205-1259

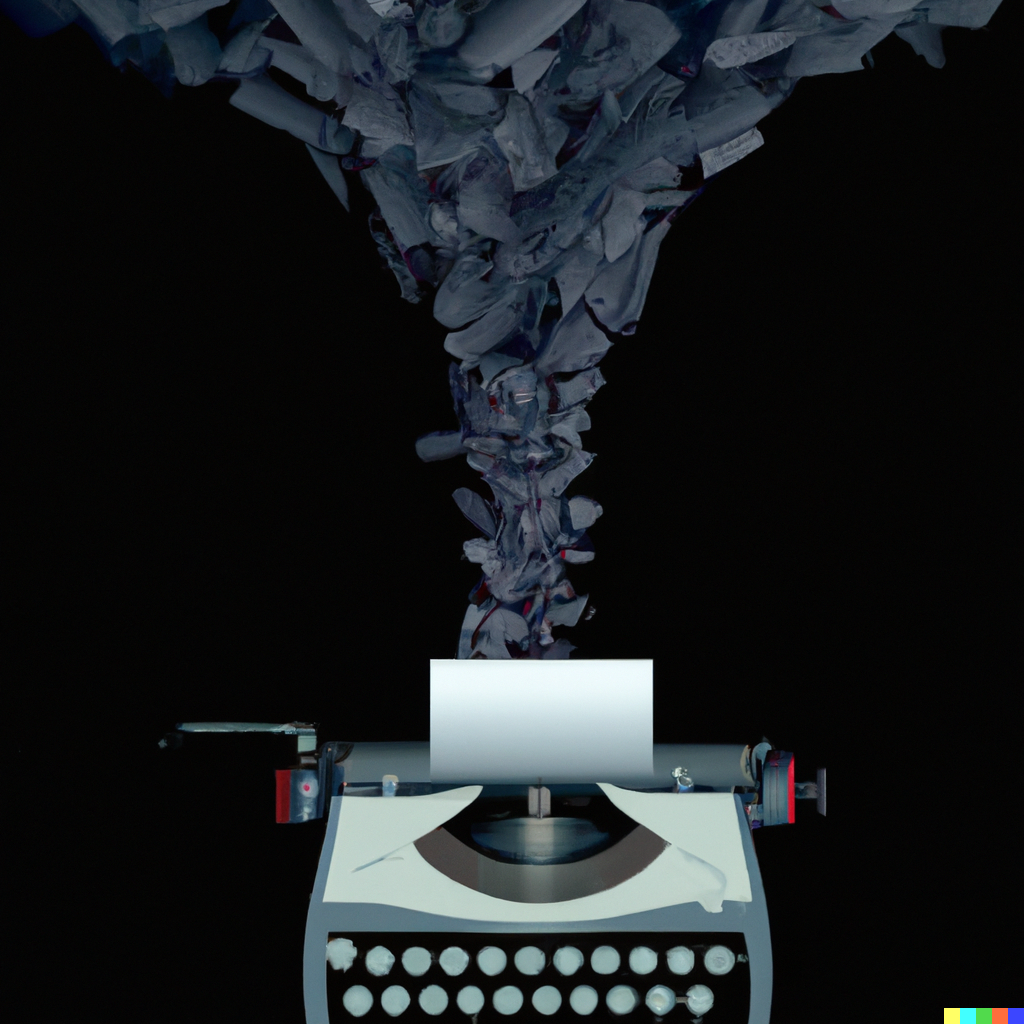

Implementing the Wisdom of Waze

Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI'15)

Working Papers

Buying Data from Consumers: The Impact of Monitoring in US Auto Insurance

What Do News Readers Want?

Working Paper

Can Usage Based Pricing Reduce Congestion?

Working Paper

Bargaining and International Reference Pricing in the Pharmaceutical Industry

Surveys, Resting Papers, Tutorials and Other Writings

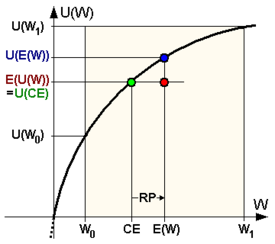

Risk Aversion and Auction Design: Theoretical and Empirical Evidence

International Journal of Industrial Organization (2021): 102758

Socioeconomic Network Heterogeneity and Pandemic Policy Response

Teaching

ECON 260: Industrial Organization III

Course combines individual meetings and student presentations, with an aim of initiating dissertation research in industrial organization.

Prerequisites: ECON 257, ECON 258

Note: Non-Economics PhD students need instructor consent

OIT 274: Data and Decisions - Base (Flipped Classroom)

Base Data and Decisions is a first-year MBA course in statistics and regression analysis. The course is taught using a flipped classroom model that combines extensive online materials with a lab-based classroom approach. Traditional lecture content will be learned through online videos, simulations, and exercises, while time spent in the classroom will be discussions, problem solving, or computer lab sessions. Content covered includes basic probability, sampling techniques, hypothesis testing, t-tests, linear regression, and simple machine learning / prediction models. The group regression project is a key component of the course, and all students will learn the statistical software package R and use the AI tools Copilot and ChatGPT.

Contact

Stanford Graduate School of Business

655 Knight Way

Stanford, CA 94305

Email: svass@stanford.edu

Faculty Assistant:

Patricia Sonora: sonorap@stanford.edu